An appreciation, by Graham Avery

Clarence Bicknell’s major work was the exploration and recording of the prehistoric rock engravings in the high valleys of Fontanalba and Meraviglie. But before he discovered archaeology, his passion was botany, and it was his botanical excursions that brought him to the high valleys.

We do not know when Clarence developed an interest in botany, but in an affluent Victorian family the naming of flowers was part of a child’s basic education. On the bookshelf may have been the classic work ‘Flowers of the Field’ by the Rev. C. A. Johns, and already before he moved to Italy Clarence owned Johns’ book ‘The forest trees of Britain’ (a copy with his signature is in the Library of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew).

Within five years of settling at Bordighera in 1878 Clarence had painted 1100 water-colours of the local flora. This was the result of excursions in the surrounding countryside, in the course of which – typically for an enthusiast of the period – he collected flowers, took them home to dry as herbarium specimens, and recorded them meticulously by painting them in water-colours. Clarence also explored the nearby mountains: already in 1881 he made an excursion with friends from San Dalmazzo to the high valley of the Meraviglie, and in 1888 he began regular visits to the Valle di Pesio where San Bartolomeo was his base for botanical excursions. Many other expatriates on the Riviera were interested in flowers: the well-known botanical garden at Mortola was created by Sir Thomas Hanbury.

BOTANICAL PUBLICATIONS

In 1885 Clarence published a selection of his paintings in the book Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera (image, left), splendidly illustrated with 82 coloured plates and accompanying notes on 280 species. He explained in the Preface that he was inspired by the British botanist J.T. Moggridge who, in a Flora of neighbouring Menton, published in London in 1864, had encouraged others to follow his example in publishing illustrations of the local flora. Clarence commented regretfully that many of the plants of the coast and adjacent mountains ‘are now to be found no more, and many others are becoming extremely scarce, owing to the ravages committed by horticulturalists’ agents and winter visitors… Every autumn, too… a new road or villa or vineyard has caused the disappearance of some favourite old friends’.

In 1885 Clarence published a selection of his paintings in the book Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera (image, left), splendidly illustrated with 82 coloured plates and accompanying notes on 280 species. He explained in the Preface that he was inspired by the British botanist J.T. Moggridge who, in a Flora of neighbouring Menton, published in London in 1864, had encouraged others to follow his example in publishing illustrations of the local flora. Clarence commented regretfully that many of the plants of the coast and adjacent mountains ‘are now to be found no more, and many others are becoming extremely scarce, owing to the ravages committed by horticulturalists’ agents and winter visitors… Every autumn, too… a new road or villa or vineyard has caused the disappearance of some favourite old friends’.

Clarence’s Flora of Bordighera and San Remo (image, right), published in 1896, was a work of reference – a list of species, drawn up on the basis of his excursions, without illustrations. His enjoyment of botanising is evident from the Preface to this book where he wrote ‘There is no part of this district which may not be visited by a good walker, with the assistance of a carriage, within a day’s excursion, and by an early start one may be among the larches, the gentians and the Edelweiss on a summer morning, and in the evening gather Oleander and Pancratium near the sea. It would be difficult to find another region of equal size with a richer or more varied flora, and after some ten years botanical expeditions I have collected over 1700 species of vascular plants’. He added wistfully ‘I think it well, with increasing years and decreasing walking powers, no longer to delay the publication of a catalogue of our plants’.

PUBLISHERS AND REVIEWERS

Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera was published by Trübner & Co, a well-established London firm specialising in books on travel, geography, and oriental literature. It had been founded in 1851 by Nicholas Trübner from Heidelberg; it later merged with Kegan Paul, and is now part of the publishing company Routledge. Clarence may have chosen Trübner because of the expertise needed for the colour lithographs, which were made by West, Newman & Co.

The Journal of Botany (British and Foreign) of London was critical of aspects of Clarence’s book, commenting that it was ‘hardly on a level scientifically with Mr Moggridge’s book’ and ‘the colour printing is fairly good, but could be better’. But it continued ‘This handsome book… is distinctly in advance of most of its class… The book is an expensive one; but there must be many who will gladly add it to their libraries… The modest tone in which Mr Bicknell writes, as well as the evidence of care taken in both drawing and description, induce us to wish well to this handsome volume’.

A reviewer in The Gardeners’ Chronicle of London commented that ‘the figures are accurate as far as they go, but they are rather the rough memoranda which the collector makes for his own use, than the detailed drawings required by the botanist’. ‘Nevertheless, from the point of view of the botanist and gardener Mr Bicknell is a benefactor of his kind, for a series of generally faithful drawings, whatever their technical defects, cannot fail to be of great service… There is then ample room for Mr Bicknell’s work, and we trust we may speedily welcome a second series’. Clarence wrote in the Preface of the book that he was ‘hoping to prepare a second series, should this first one be found to meet a want’. But he did not produce another work of the same kind.

Flora of Bordighera and San Remo, published by Pietro Gibelli of Bordighera, was not reviewed in British journals. Gibelli was the publisher of a range of books in Italian, French and English, as well as postcards and maps; he published two of Clarence’s books on rock engravings, and two of his works in Esperanto. In 1914. Clarence received a visit from Gibelli’s wife and daughter at his summer home, Casa Fontanalba.

BOTANICAL FRIENDS

In his book of 1896 Clarence wrote ‘I greatly wish that more of our winter visitors, both at Bordighera and San Remo, would send me the plants they find, however common… I shall always be grateful for specimens, as well as corrections of any of the numerous errors into which I have probably fallen, in this extreme corner of Italy with only a small botanical library and far from Herbaria and from fellow-workers’.

Clarence had, nevertheless, many botanical acquaintances. In the Preface of his 1885 book he thanked particularly his friend Francesco Panizzi of San Remo, and other botanists at Pisa, Genoa, Turin, Geneva, and the President of the Linnaean Society in London. Francesco Panizzi, who had a pharmaceutical establishment in San Remo, was a proficient botanist who discovered a number of new species: Narcissus panizzianus is named after him. In his 1896 book Clarence lamented that ‘the Herbarium of my friend the late Cav. F. Panizzi, which his son has kindly placed at my disposal, has been sadly neglected, and vast numbers of plants have been destroyed by insects beyond all possibility of recognition’.

Already in 1883 the botanical expertise of Panizzi and Bicknell was mentioned in the book San Remo climatically and medically considered by Arthur Hill Hassall, to which Clarence contributed a ‘classified list of most of the principal Flowering Plants’. Hill was a British physician specialising in tuberculosis, who had founded the sanatorium at Ventnor in the Isle of Wight and settled in San Remo in 1878.

Clarence Bicknell’s most significant botanical friendship was with the Swiss botanist Emile Burnat (1828-1920)(image,right), described by Reginald Farrer in 1911 as ‘the greatest authority on the flora of the Maritime Alps’. Burnat’s monumental Flore des Alpes Maritimes (image, left) was published in Geneva in six volumes from 1892 to 1917, with a posthumous volume added in 1931

Clarence Bicknell’s most significant botanical friendship was with the Swiss botanist Emile Burnat (1828-1920)(image,right), described by Reginald Farrer in 1911 as ‘the greatest authority on the flora of the Maritime Alps’. Burnat’s monumental Flore des Alpes Maritimes (image, left) was published in Geneva in six volumes from 1892 to 1917, with a posthumous volume added in 1931

In the Introduction to Flora of Bordighera and San Remo Clarence thanked ‘the many eminent botanists who have assisted me in the determination of species, for which my knowledge was insufficient, and among these chiefly Monsieur Emile Burnat, whose exhaustive work on the flora of the Maritime Alps is now in course of publication’. For his part, Burnat in Volume 1 of the Flore thanked « mon ami M. Cl. Bicknell (auteur de Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera…) établi à Bordighera, lequel m’a depuis six années communiqué de nombreuses plantes de diverses parties des Alpes maritimes, dont plusieurs nouvelles pour ma Flore » (“my friend Clarence Bicknell… of Bordighera, who in the past six years has sent me many plants from various parts of the Maritime Alps, including several new species”).

In Volume 4 Burnat wrote « Notre excellent ami, M. Cl. Bicknell, n’a cessé de nous donner un bienveillant concours en nous envoyant, avec ses meilleures récoltes, de nombreuses observations » (‘our excellent friend Clarence Bicknell has continued his kind assistance by sending us numerous observations, together with the best specimens that he collects’). The volumes of Burnat’s Flore include hundreds of citations of Clarence Bicknell, and more than a thousand of the specimens listed in the catalogue of Burnat’s Herbier in Geneva were provided by Clarence.

A younger friend was Dr Fritz Mader, son of the German Lutheran priest at Nice: he was an alpinist and an archaeologist as well as a botanist (he corresponded with Burnat), and every summer he stayed in the mountains at Tende. His publications included Excursions in the Maritime Alps (published by the Italian Alpine Club in 1896 in Italian), Illustrated Guide to the French Riviera (1900 in German), and a survey of gardens in the Maritime Alps (1912 in French). Clarence Bicknell wrote that in 1902 he escorted to Val Fontanalba ‘Dr Fritz Mader of Nice, the author of the excellent German guide to the Maritime Alps, and Herr Alwin Berger, curator of Sir Thomas Hanbury’s garden at La Mortola’.

BOTANISTS AT CASA FONTANALBA

From 1906 onwards Clarence received visits from amateur and professional botanists at his summer home in the mountains, Casa Fontanalba, where their names were recorded in the Visitors Book. In 1909 Emile Burnat, then aged 79, appears in the Visitors Book accompanied by his son Jean Burnat, Francois Cavillier, John Briquet and Emile Abrezol. This was a veritable galaxy of botanical talent from Geneva, where Briquet was head of the Botanical Garden and Cavillier was an assistant. They had worked with Burnat for many years, and were to complete his Flore as co-authors of the later volumes, and also to edit his autobiography. Abrezol was another assistant.

Another eminent Swiss botanist Henry Correvon (author of Atlas de la Flore Alpine) visited Casa Fontalba in 1914. Fritz Mader’s name appears in the Visitors Book in 1906, 1909, and in 1911 accompanied by Marie Mader (probably his sister).

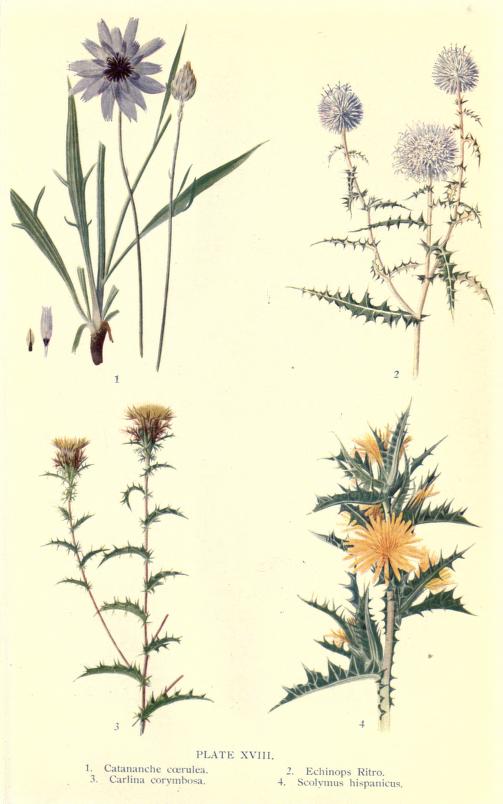

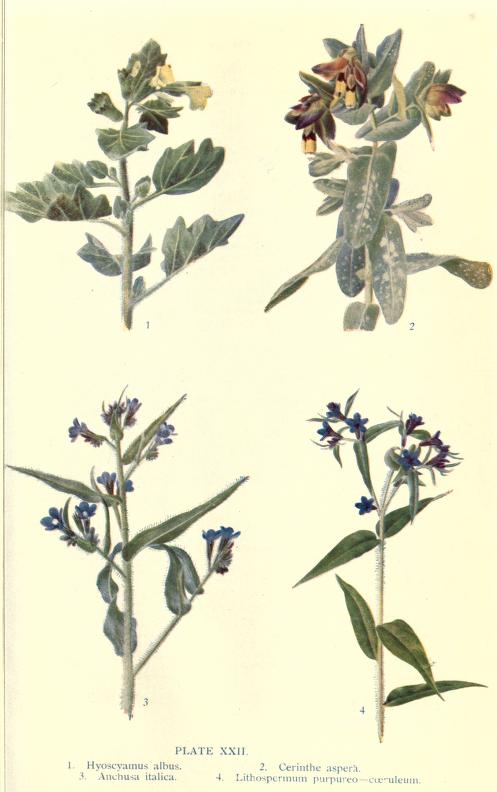

The British botanist Harold Stuart Thompson visited Casa Fontanalba in 1907. In 1914 Thompson published Flowering Plants of the Riviera (image, left) in which the 24 coloured plates were reproductions of water-colours by Clarence (images of plates 18 and 22, below right). Commenting in his Preface on existing botanical literature, he wrote that ‘the splendid work of M. Emile Burnat (Flore des Alpes Maritimes) does not make the progress we should like to see: [only] four volumes have appeared’, and that he had ‘found Mr Clarence Bicknell’s large illustrated volume (now out of print) entitled Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera very helpful… and the same writer’s Flora of Bordighera and San Remo… contains many original notes of great value’.

The British botanist Harold Stuart Thompson visited Casa Fontanalba in 1907. In 1914 Thompson published Flowering Plants of the Riviera (image, left) in which the 24 coloured plates were reproductions of water-colours by Clarence (images of plates 18 and 22, below right). Commenting in his Preface on existing botanical literature, he wrote that ‘the splendid work of M. Emile Burnat (Flore des Alpes Maritimes) does not make the progress we should like to see: [only] four volumes have appeared’, and that he had ‘found Mr Clarence Bicknell’s large illustrated volume (now out of print) entitled Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera very helpful… and the same writer’s Flora of Bordighera and San Remo… contains many original notes of great value’.

Reviewing Thompson’s book, the Journal of Botany (British and Foreign) of London commented that readers ‘will be aided in their work by the coloured figures, much reduced from the admirable drawings of Mr Clarence Bicknell… Those who know Mr Bicknell’s volume published in 1885… will share with us the hope that more of his drawings may be reproduced in a style worthy of the originals’.

Reviewing Thompson’s book, the Journal of Botany (British and Foreign) of London commented that readers ‘will be aided in their work by the coloured figures, much reduced from the admirable drawings of Mr Clarence Bicknell… Those who know Mr Bicknell’s volume published in 1885… will share with us the hope that more of his drawings may be reproduced in a style worthy of the originals’.

At Casa Fontanalba in 1910 Clarence received the British plant collectors Reginald Farrer and Clarence Elliott. Farrer recalled this encounter in his book Among The Hills, and in The English Rock-Garden he recommended a visit to the valley occupied by ‘a famous English botanist, one Mr Bicknell, who has there a house and spends long summers, in the course of which he asks nothing better than to show the treasures of his hills to all such fellow-collectors as desire to see them’. For more on this see ‘Clarence Bicknell and Reginald Farrer, 19 July 1910’, download here).

ALPINE GARDENS

Clarence created a small garden at Casa Fontanalba with local flower species, which he recorded in an album with water-colour paintings and botanical notes. In the Visitors Book for Casa Fontanalba he included a flower-painting for each special guest. Botanical themes figure in the mural decoration that Clarence executed for the interior of the house, and for his friend Margaret Berry he designed a botanical version of the popular card game ‘Happy Families’, with cards depicting 16 flower-families.

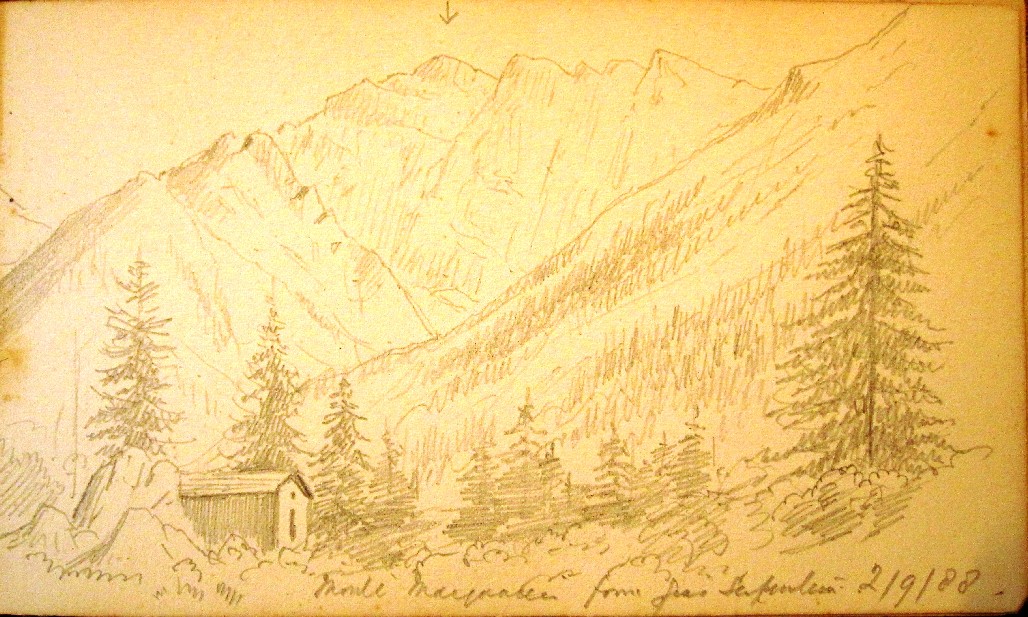

Clarence visited regularly the alpine valley of Valle di Pesio, north-east of Tende, which was also Emile Burnat’s base for botanical campaigns. Italy’s Parco naturale del Marguareis maintains there a nature reserve that commemorates the work of both men. Further information is available in the document ‘Botanical Reserve ‘E. Burnat / C. Bicknell’ on this web site which can be downloaded here.The nature reserve Stazione Botanica Alpina E. Burnat / C. Bicknell, at Pian del Lupo high up on the slopes of Monte Marguareis, protects rare and threatened habitats and high-mountain plants endemic to the region. It is reached from Pian delle Gore at 1000 metres by a path that goes up through the Sestrera valley to the botanical reserve at 1980 metres (photo, right). Emile Burnat made his summer camp in the Sestrera valley, and from the nearby Serpentera valley Clarence Bicknell made a sketch of Monte Marguareis on September 2nd 1888 (image, left).

Clarence visited regularly the alpine valley of Valle di Pesio, north-east of Tende, which was also Emile Burnat’s base for botanical campaigns. Italy’s Parco naturale del Marguareis maintains there a nature reserve that commemorates the work of both men. Further information is available in the document ‘Botanical Reserve ‘E. Burnat / C. Bicknell’ on this web site which can be downloaded here.The nature reserve Stazione Botanica Alpina E. Burnat / C. Bicknell, at Pian del Lupo high up on the slopes of Monte Marguareis, protects rare and threatened habitats and high-mountain plants endemic to the region. It is reached from Pian delle Gore at 1000 metres by a path that goes up through the Sestrera valley to the botanical reserve at 1980 metres (photo, right). Emile Burnat made his summer camp in the Sestrera valley, and from the nearby Serpentera valley Clarence Bicknell made a sketch of Monte Marguareis on September 2nd 1888 (image, left).

FROM BOTANY TO ARCHAEOLOGY

It was botany that brought Clarence to the high valleys and the rock figures. In his Preface to The prehistoric rock engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps (1902, pages 5-6) he wrote ‘I am only an amateur botanist, and have gone up into these neighbouring mountains in my summer holidays in order to study their Flora; but the fascination of the rocks has made me neglect my special hobby; and I have spent the greater part of my time in making drawings and taking notes of the rock figures’.

In A guide to the prehistoric rock engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps (1913, page 26) Clarence explained that after his visits to the valley of the Meraviglie in 1881 and 1885 ‘in 1897 I heard that a house in Val Casterino… was to be let and I took it for the summer, partly with the intention of botanising, but partly with that of seeing more of the rock figures’. Later he built his home Casa Fontanalba there.

Clarence’s experience as a botanist contributed to his work as an archaeologist. His predecessors in the study of the rock engravings had developed speculative theories about their origin, giving priority to historical interpretation rather than methodical description. But botanists do not interpret flowers, they describe them. It was Clarence’s meticulous drawing, photographing, recording, listing, classifying and publishing of the rock-figures that helped to bring them out of the obscurity of antiquarian speculation into the light of scientific investigation and analysis. Although Clarence devoted many years to botany, it was his work on rock art that brought him fame. The field of botany was already well cultivated; in the field of prehistory he was able to pioneer new techniques and disseminate new information.

Clarence’s experience as a botanist contributed to his work as an archaeologist. His predecessors in the study of the rock engravings had developed speculative theories about their origin, giving priority to historical interpretation rather than methodical description. But botanists do not interpret flowers, they describe them. It was Clarence’s meticulous drawing, photographing, recording, listing, classifying and publishing of the rock-figures that helped to bring them out of the obscurity of antiquarian speculation into the light of scientific investigation and analysis. Although Clarence devoted many years to botany, it was his work on rock art that brought him fame. The field of botany was already well cultivated; in the field of prehistory he was able to pioneer new techniques and disseminate new information.

Describing the local flora in A guide to the prehistoric rock engravings in the Italian Maritime Alps he wrote (page 11) ‘there are a good many plants in the neighbourhood peculiar to the Maritime Alps, but the flora is not so rich as it would be if there were more calcareous rock’. After listing a number of species he continued “Edelweiss, the much overrated flower, called in Italy Stella d’Italia, to gather which so many lose their lives in Switzerland and elsewhere, is the commonest of common plants on the limestone. The glory of the Maritime Alps Saxifraga florulenta is to be found on vertical cliffs in Val Fontanalba and in Val Valmasca, the latter being the habitat farthest east at present known”

Known in English as ‘The Ancient King’, the rare and spectacular Saxifraga florulenta grows only in the Maritime Alps, in inaccessible places. Once in its life it sends up a big flower-spike, and then dies. It was adopted as the emblem of France’s Parc National de Mercantour which is responsible for the protection of the region. The watercolour by Clarence to the right is in the collection he gave to the University of Genoa, whom we thank for the right to reproduce the image.

CLARENCE BICKNELL’S BOTANICAL LEGACY

Clarence’s legacy to botanical science includes his books, his paintings, his herbarium, and his contribution to knowledge of the flora of his region in which he lived.

His book Flowering plants and ferns of the Riviera contains outstandingly beautiful images, and his book Flora of Bordighera and San Remo is a comprehensive catalogue of local species, and was innovative in including their names in local dialect. He gave many books to the Biblioteca Bicknell in Bordighera; about a third of its volumes for the period from 1880 to 1910 are botanical works, including his own publications and those of his botanical friends.

He made more than 3000 flower paintings, of which many are preserved in the Hanbury Institute at the University of Genoa. The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has more than 400 of his designs, sketches and drawings of flowers. The University of Genoa has 247 packets of his dried specimens, while the Museo Bicknell has 48 packets with a total of 11,216 folio sheets.

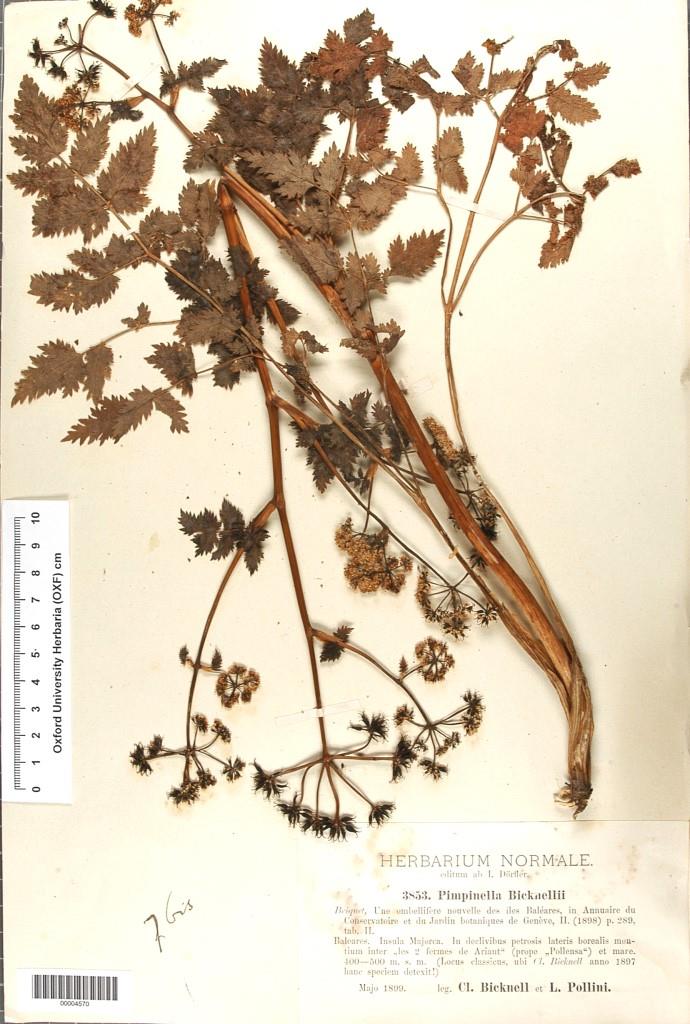

This sample of Pimpinella bicknellii collected by Clarence Bicknell and Pollini is in the Oxford University Herbaria whom we thank for the rights to reproduce the image.His role in recording the flora of the Maritime Alps was significant: he identified many new sites of rare or endemic plants, he added 73 species to those known to grow in Liguria, and he was the first to identify an Italian site of the species Sempervivum calcareum.

Addendum of January 2016 (MB editor): The Oxford University Herbaria has many specimens of flowers collected and pressed by Bicknell and contributed by correspondents other than him. The network of researcher/collectors across Europe and elsewhere was a significant feature of the explosion of interest in science and nature in the second half of the 19th century. Bicknell himself corresponded with scores of botanists and archaeologists in English, French, Italian and Esperanto and he was a dedicated European 150 years before the Union we know today. The image to the left here is of a plant named after him, Pimpinella bicknellii, and collected by him and his faithful helper Luigi Pollini. This plant, endemic to Majorca, was named after Bicknell in 1898 by John Briquet, Director of the Botanical Garden of Geneva. The specimen at Oxford University has a label of the Herbarium Normale of Ignaz Dörfler stating (in botanical Latin) that it was “collected by Clarence Bicknell and Luigi Pollini in May 1899 on Majorca at a height of 4-500 metres on rocky slopes on the northern side of the hills between the two farms of Ariant (near Pollenza) and the sea, the locus classicus where Bicknell first discovered it in 1897”.

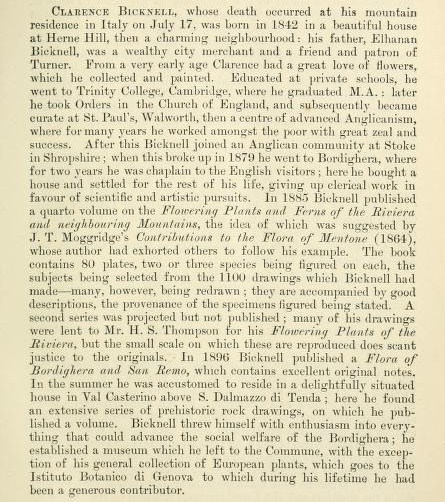

On Clarence’s death in 1918 James Britten, editor of the Journal of Botany (British and Foreign) of London published a respectful obituary. Clarence was even better known in botanical circles in other European countries, where his contribution to the scientific recording of the flora of his region was widely appreciated.

For more from Graham Avery on these topics, see

For more from Graham Avery on these topics, see

“Clarence Bicknell and Reginald Farrer, 19 July 1910” – download here

“Oxford Herbaria and Clarence Bicknell” – download here.

“Aileen Fox, archaeologist, at Casa Fontanalba in 1927 and 1928” – download here

Graham Avery, 9th April 2013

Graham Avery writes in 2016: So far I have identified four plants named after Clarence Bicknell: I already knew of Euphrasia bicknellii Wettstein and Pimpinella bicknellii Briquet (see my note ‘Kew & Clarence Bicknell’) and I have now discovered Rhaponticum heleniifolium subsp. bicknellii (Briq.) Greuter and Dorycnium bicknellianum Beiger et Dinter. Also, the ant Iridomyrmex bicknelli was named after Clarence.

Other related articles by Graham Avery on this web site:

Augusto Béguinot on Clarence Bicknell (1931)

Belgium’s Botanic Garden and Clarence Bicknell

The Bristol Botanists at the Casa Fontanalba (2017)

Clarence Bicknell – Botanical Exchanges

Clarence Bicknell – Botany and the Hanbury Gardens

Clarence Bicknell – Correspondence with Emile Burnat (1886-1917)

Clarence Bicknell – Kew Gardens

Clarence Bicknell – Moggridge and Moggridge

Clarence Bicknell – Pimpinella bicknellii

Clarence Bicknell – Reginald Farrer (1910)

Clarence Bicknell – Stefano Sommier

Oxford Herbaria and Clarence Bicknell

The E. Burnat / C. Bicknell Nature Reserve in the Marguareis Natural Park

The Tasmanian Ant, Iridomyrmex bicknelli (1898)

About the author:

Graham Avery C.M.G. is Vice-Chairman of the Clarence Bicknell Association, Fellow of the Linnean Society of London, and Honorary Director-General of the European Commission, Brussels. He has been Secretary General of the Trans European Policy Studies Association, Fellow at the Center for International Affairs at Harvard University, Fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute, Florence, and Senior Member of St. Antony’s College and of Mansfield College, Oxford University.